Unilateral idealism

Using state-of-the-art techniques NSU decided forty years ago to create an innovative medium-size sedan. It was to be the Ro 80's origin. The Wankel rotary engine that propelled this famous car dates 50 years back. Two jubilees in one car, what more reason do we need to go and taste the atmosphere in the German Neckar Valley, where both the car and the engine were conceived?

Text by Robert van Overbeeke, photography by Lucas Verbeke, translation Robert van Overbeeke

After a period of near-stationary life in traffic jams the Ro 80's engine gradually spins better and better on the German autobahn. Every time a lorry suddenly changes lanes and ends up right in front of our car, necessitating us to slam on the brakes full force, the big NSU needs less and less time to go back to cruising speed. The engine is strikingly silent at engine speeds around 5.000 rpm. The tires are audible enough, unfortunately. Would that be due to the fact that they are modern 'hard' Michelins Energy or would the original Michelins XAS have been just as loud? The German autobahns are no longer the smooth billiard-like sheets of asphalt they used to be. Re-uniting former East and West Germany has devoured the budget for road maintenance. Back in the sixties and seventies, when the Ro 80 was on the market, things were quite different. The best asphalt was to be found in Germany and that was the place to go if you loved fah'n fah'n, fah'n auf der Autobahn (high speed cruising). These days the French have the best asphalt. How things change…

The silence is also disturbed by the strong hissing sounds emanating from the air vents that are wide open on this hot day – a pity, really. We are on our way to the Neckar Valley/Odenwald National Park in the South of Germany, due North of Neckarsulm, the city where the NSU-works used to be. That is to say: the plant is still there, but it is operating under the Audi-banner now. Here the R8's, Quattro's and RS's are built. The other Audis come from Ingolstadt.

By the end of the sixties the NSU Ro 80 was nothing less than avant-garde. And that is exactly how it was meant. NSU had done well since the end of World War II, churning out thousands of small utility vehicles, motorcycles and cars alike. Now the time had come to move up in the hierarchy of car manufacturers and introduce a bigger model, preferably one that had everything the competitors did not have. In order to establish a firm position on the market the car had to be state-of-the-art in all respects right from the onset.

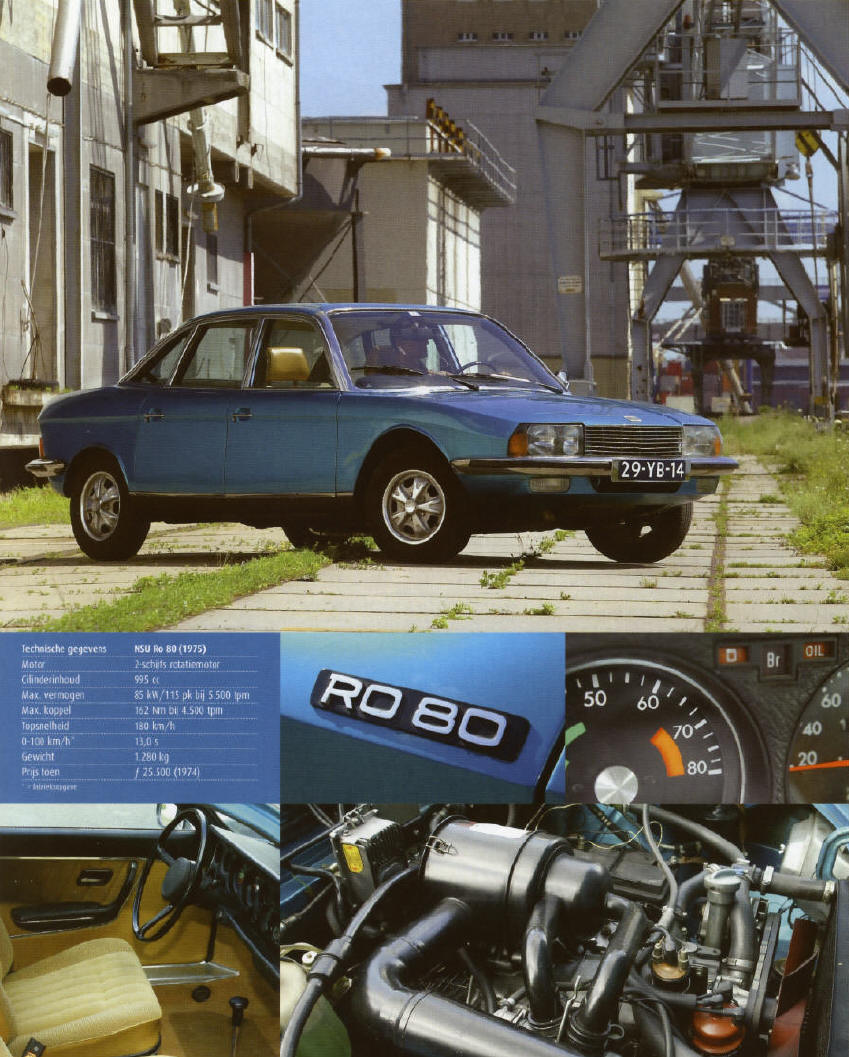

The wedge-shaped dynamic exterior was a good starting-point – it was really something else in a time when square lines and sharp edges were in fashion. Think for instance of contemporaries like the Mercedes 200-series (W114/115), the BMW 2000, the Rover P6 2-litre, the Alfa Berlina and the Audi 100. The only competitor with an equally futuristic appearance was the Citroen DS, but that car was conceived almost a decade earlier.

The Ro 80 was designed by a team headed by Claus Luthe, who would later be head of design with BMW, where he would be responsible for the first 5-series, 3-series and 7-series. How far ahead of its time the design really was, can still be appreciated when you peer at the big NSU through semi-shut eyes. Partly due to the third side window and the long wheelbase you tend to mistake the car for the previous generation Audi A6 or an earlier model Volkswagen Passat. You would never think it was a 40-year old design at any rate. The wedge shape still is the leading principle for today's saloons.

The gradually rising shape ensures stable road-holding capacities at high speeds. The low front end gets 'under the wind' thereby generating pressure on the front wheels. The tall rear end also has the effect of a spoiler, generating pressure on the rear wheels. The absence of external trim, together with the rounded nose helps keeping the Cx-value low – 0,355 was exceptionally good in those days.

Inspiration

Cruising at 90-100 mph is a pleasant experience in the Ro 80, the engine

being barely audible. Under the bonnet things are really revolutionary. No

stamping pistons there. Two triangular discs that spin in a circular casing

form the heart of the engine. How on earth can anyone think of such a

concept? The inspiration sprouted in the brain of Felix Wankel (1902-1988),

a self-made engineer who as an adolescent had the idea that in order to

achieve a spinning motion of the wheels it would be more efficient to start

off with a spinning motion in the engine. Converting an up-and-down going

motion into a spinning one, as conventional engines do, means loss of

energy. Moreover in an up-and-downward motion the pistons come to a halt

every time they change direction, the so-called top and bottom dead centres.

Wankel spent all his life realizing his idea. In the fifties he met Dr.

Walter Froede, head of the NSU R&D-department, and both gentlemen decided to

co-operate.

After several successful experiments using the rotary engine in NSU-race bikes their attention was turned to cars. Both Wankel and Froede were so convinced of the engine's capacities that they hazarded a 1.000-hour test (i.e. nearly six weeks non-stop!) at full throttle instead of the usual 500-hour test. At the time a conventional piston engine would never have endured such a treatment. Using an intercom system Froede listened in on how the engine was doing. At the first attempt it lasted a whopping 990 hours! Then a rotor tip seal blew, costing just pennies. A second attempt ensued. After six weeks of monotonous whirring and increasing tension in the NSU works there it was: the rotary engine had completed 1.000 hours at full throttle without any problems whatsoever!

In 1957 the engine was deemed ready for production. First it was mounted in an existing model, the Prinz Spider, which was duly re-baptized Wankel Spider. After sufficient experience had been accumulated NSU felt that the Wankel engine would be suitable for the groundbreaking model that was being developed. That car was already loaded with technological innovations. The futuristic engine would complete the picture nicely. The rotary engine's main characteristic of performing well and silently at high revolutions made it perfectly suitable for long distance cruising at high speeds, especially combined with the aerodynamically shaped body.

The Ro 80 sports independent suspension and McPherson-struts all around, not

a common solution in those days. Thanks to the long wheelbase (2.86 m) it

merely bobs along gently when encountering long undulations, like a

limousine would. The platform can cope with high speeds easily and exhibits

no trace of unease. Damping is reminiscent of the Ro's contemporary French

rivals, due to the long wheel-travel and the soft set-up. We know we are in

a German car, but you could fool us into believing it is French.

The steering is equally without vibrations or other flaws. The big NSU seems

to ride on railway tracks. The power steering does not assist too strongly

and the steering wheel needs some coaxing to make the car change course – a

useful characteristic for motorway use.

The seating in the front of the car is majestic, although you find yourself a little close to the steering wheel in order to reach the pedals; this is even so for tall persons. Due to the absence of a transmission tunnel or centre console there is ample space. The front seats feel comfortably soft, but under cornering transform themselves into sporty bucket seats that firmly grip your hips. Passengers in the back of the car have plenty of space too, and boot space measures even a whopping 580 litres. The backrest is divided in two individual parts. Both parts come out, leaving a 30 cm wide gap on both sides of the central armrest, to accommodate several pairs of skis for example.

All in all the Ro 80 is first and foremost a comfortable long distance cruiser, capable of transporting its passengers in relative silence at high speeds. Pity it did not come with air-con or cruise control…

Friendliness without self-interest

On the way to our destination we must have passed a language barrier, because from the moment we check in at the hotel we hear nothing but the Southern-German accent with lots of friendly sh-sounds and a near-French intonation. Every other sentence ends in a questioning 'gel?' ('isn’t it?'). This version of German is rarely heard on our beaches come summertime.

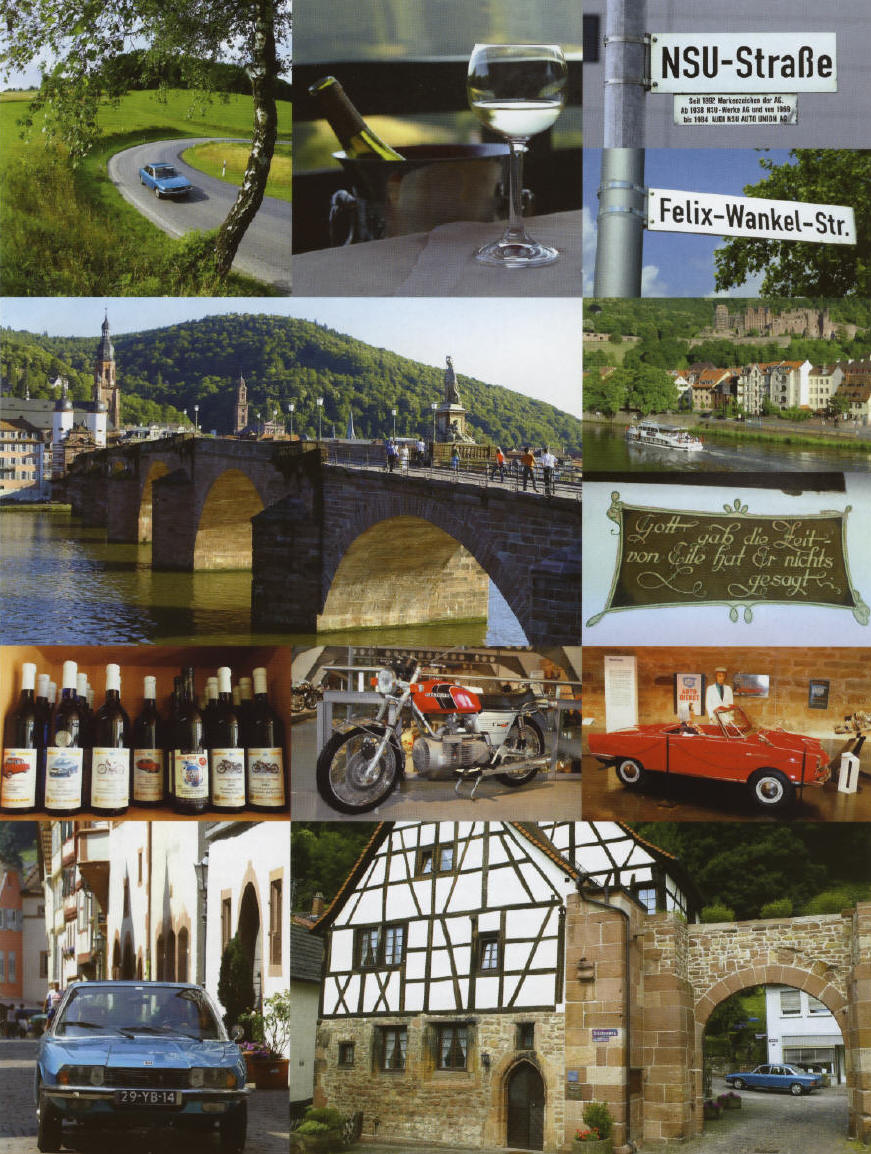

The friendliness of the local population stretches far and is entirely without self-interest. We experience this personally when we suddenly realize one of our bags is still in the NSU Museum after closing time. The neighbour at the wine merchants' guild phones all Neckarsulm up and finally sends in the Notdienst (similar to the fire brigade) to free our unfortunate bag. In the meantime he offers us wine, water and some crisps. He refuses all kind of compensation for his trouble.

The Neckar Valley/Odenwald National Park is situated next to the industrial zone of Mannheim-Ludwigshafen, which is full of chemical plants. The Neckar joins the Rhine river there. Drive through a long tunnel and suddenly find yourself in this green oasis. What a contrast! Our hotel is located some twelve miles deep in this area, on a hillcrest, the Kreidacher Höhe near the village of Wald-Michelbach. The chalet-style accommodation is one of the few around sporting both an outdoor and indoor swimming pool. It is not only us who value this, last June the Audi Le Mans-team evaluated their last win here.

The splendid view from our rooms reveals rolling hills. In the valley below we can hear drivers of cars and motorbikes enjoying the winding roads. Test-drivers from the nearby Mercedes-, Audi- and Opel-works use the area regularly, the hotel cook tells us. From his fine menu we select trout in Riesling-sauce, stewed in shallots, white wine, cream and sauce hollandaise, followed by a venison steak with fresh mushrooms and cranberries. The photographer chooses pfifferlinge (spring mushrooms) and carpaccio of tomato, while his main course consists of salmon trout with nettle-meringue and asparagus. The accompanying local dry 2005 Heppenheimer Centgericht 'Burgstrasse', a Grauburgunder Spätlese, is a real treat. The staff serves us in distinguished style without being unduly formal.

Typical two-stroke behaviour

The engine needs to be fed just as well as we do. After the trip to the

South of Germany we check the oil level. Not only does the engine burn

petrol, it also burns some oil. According to the manual it uses 1 litre

every 800-1.000 kilometres (500-600 miles). Sometimes you can actually see

it burning oil, especially when starting the car while the engine is still

cold: blue fumes emanate from the exhaust-pipe. An advantage of the system

is that the oil never needs changing; a disadvantage is that it needs

expensive, fully synthetic oil. On the other hand it accepts cheap,

unleaded, low-octane petrol (octane 91). Yes: unleaded, because the main

purpose of lead in petrol is to lubricate the valves of an engine, but the

rotary engine has no valves. Nor camshafts, for that matter. This means less

driving-gear noise and no adjusting of valve play ever. Our oil consumption

on the way to the Neckar Valley appears to be nearly 1.200 kilometres to the

litre – not bad.

Not only this running on a mix of oil and petrol is reminiscent of two-stroke engines, so is the sound when starting the engine, when idling or at low revs. It is strewn with irregular spluttering, just like a Trabant form former East Germany does. When starting the engine when cold you even think all hell is breaking loose. Back in the seventies the neighbours must have been pleased when the Ro's engine was started at 7 a.m.!

Even driving the Ro is like driving a car with a two-stroke engine. When the local authorities have set a speed of 80 km/h (50 mph), like they have on the Burgenstrasse along the Neckar river, the Ro clearly does not appreciate this en rocks slightly in protest. It wants more revs, as if it means to say: "Come on, press that accelerator, let's get on with it!" Maybe an extra gear between second and third would have solved this. You end up alternately pressing the accelerator and releasing it – typical behaviour for two-stroke engines.

Last but by no means least another two-stroke characteristic is that the spark plugs regularly need to be burned clean, on the German autobahn for instance. A Ro that spends most of its time in traffic jams or in town traffic will inevitably end up with oiled-up spark plugs.

The engine is at its best when revving it hard. The splutter disappears, the engine tone becomes like that of a six-cylinder, it runs really smoothly and – compliments of the torque converter – it pulls like a horse. A soft whistling accompanies the turbine-like sound and increases temporarily whenever you change gear, not dissimilar to a turbocharger that gets rid of excess pressure; nice!

Premature

The Ro 80 is a car not to be used without consulting the manual. It is not

suited as a runabout for granny, not now, nor back in its day, compared to

contemporary rivals. Those rivals were a lot easier to drive, with the

possible exception of the Citroën DS. So in this respect NSU did not succeed

in making the near-perfect car they were aiming for.

Changing gears in the peculiar NSU wants some instruction too. The semi-automatic three-speed Fichtel & Sachs gearbox, similar to the one Porsche used for the 911 Sportomatic in those days, needs some getting used to. There is no clutch pedal. The connection between gearbox and engine is electro-pneumatically disengaged as soon as you touch the gearlever. A sensor in the gearlever takes care of that; the vacuum created by the engine operates the clutch. As stated earlier, it is a pity there are only three speeds. The 2.000-rpm drop when switching gears under acceleration is just a tad too big. Ideally the revs are kept between 4.000 and 5.500 rpm. That is when the engine turns at its best. During daily driving the second and third gears are used most often; it is even perfectly possible to take off in second. Gear-changes usually proceed smoothly. Only putting the 'box in first requires a little too much effort. Sometimes you feel as if you are mistreating first gear. Indeed it protests now and then, especially when the engine is idling and you try to put the 'box in first gear.

Don't get us wrong, the Ro 80 is not an unpleasant car at all. On the contrary, but because the car is so close to perfection, just as the manufacturer desired, one tends to start thinking how it could be brought even closer to perfection. During the couple of days we spend with the car, we get several ideas how it could be improved. In most cases these ideas concern the driveline. For example: more power, more torque at low revs, petrol-injection, a fully automatic gearbox… The driveline now sometimes makes you wonder who is the boss: the driver or the mechanicals? It is only on the motorway you forget you are driving a car with an engine that is fundamentally different from all others.

Had the NSU-engineers been able to use techniques of today a lot more would have been possible. Think of the TSI-concept Volkswagen-Audi are using: a mechanically driven compressor to boost power at low revs and a turbocharger for more power at high revs. Also think of electronic engine-management, the twin-clutch automatic gearbox …

In order to check our ideas, we borrowed a Mazda RX-8, the only rotary engine driven car currently on the market, and compared it to the Ro 80. At idle the Mazda's engine is just as docile as a conventional one; at constant low speeds the Ro 80's rocking is absent. The irregular spluttering when starting a cold engine is there, however, but thorough soundproofing makes this barely perceptible. Civilizing the engine's running at low speeds has made the use of a torque converter to dampen irregularities superfluous: therefore the Mazda comes with a sporty manual gearbox. Keep the revs between 4.000 and 10.000 rpm (no, this is no mistake) and you have a fantastically performing engine. The sounds it produces at these engine speeds are almost similar to those of a Formula 1 car. Obviously the rotary engine can be tamed perfectly with today's knowledge. So in this sense too the NSU's rotary was way ahead of its time, may be even premature.

Nibelungen

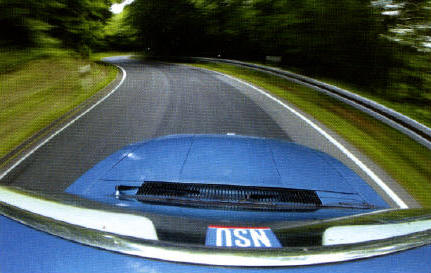

Although the Odenwald is not exactly the motorway, driving the Ro 80 there

is great. Just keep up the revs – around 5.000 rpm – and enjoy the corners.

The engine produces sounds like a jet engine and seems to be thoroughly

enjoying itself too. Of course the car is not meant for this way of driving

and it shows. There is lots of body-roll, yet it lets itself be swept up the

hills valiantly. Going downhill is not a problem either. There are four ATE

power-assisted disc brakes to stop the NSU. Steering is no chore; under

these circumstances the power-assistance works for you.

The picturesque villages are full of traditional Fachwerk-style dwellings, market-squares with ancient water pumps, Gaststubes (pubs) with Biergartens, adorned with uh… grapevines and gothic lettering – just as you would expect. The engine sound reverberates beautifully off the walls in the streets, a warm muffled growl at these low engine speeds, that makes the villagers briefly raise their heads. As soon as we park the car there is always someone who comes to express his surprise at seeing a running Ro 80. Within seconds the classical running gag is recounted that owners of a Ro 80 used to signal to each other how many engines they have had mounted by raising the corresponding amount of fingers. (The engine did not have the best of reputations in the early production years. That all teething troubles were overcome by 1970 unfortunately never reached the public. By that time potential buyers had all turned their backs on the big NSU.)

The itinerary of the Nibelungen, a people from the Middle Ages, runs right across the Odenwald. Legend has it that the Nibelungen crossed this area on their way to Hungary. There is a Nibelungenstrasse and a Siegfriedstrasse. At least five municipalities claim to have within their boundaries the well where Siegfried was murdered. In the 19th century Wagner, the German composer, used the legend's tale haphazardly and blended it with ancient Germanic deities to form a version of his own: the famous 'Ring des Nibelungen' opera cycle. A couple of decades later Hitler, who was an admirer of Wagner's, used elements from the saga to try and unite the German people.

Neckar and Sulm

We are on our way to the city of Neckarsulm, where the Sulm river joins the Neckar – hence the name. This is where the Ro 80 was conceived and manufactured. The road along the Neckar is romantic, with lots of long curves, running along several small castles and wooded hillsides. For tourist purposes it is a bit too frequented, but for those who love driving without stopping to admire the scenery the so-called Burgenstrasse is good fun.

In Neckarsulm the Audi-plant can hardly be missed. It is good to see the road where the plant is situated is called NSU-Strasse and has a Felix Wankelstrasse as a side street. A little further down the road is the 'Zweirad- und NSU-Museum', which presents mainly an overview of motorcycles from various manufacturers. There is hardly any NSU four-wheeler to be found and the only Ro 80 within the walls is not even complete…

All in all the Ro 80 was a well-built car. The engine was unfortunately a little too futuristic and not quite ready for production. It took the whole of three years to solve the teething problems. By that time the reputation of the car had gone to smithereens. The main problem was that the engine was not foolproof: misuse could lead to blowing it. Even the generous 30.000 kilometre warranty (20.000 miles) did not help. NSU had not taken into account the general public's mentality. Part of the public deliberately blew sound engines when the warranty's end was due in order to obtain a fresh one. Soon NSU was on the brink of bankruptcy. In 1969 Audi took over.

From October 1967 until April 1977 37.402 Ro 80's were built. By the time the car's production ended a more potent engine (type 871) was ready to enter production. At some stage Audi considered using this new Wankel engine in the Audi 100/200-series. But in 1977 production of the Ro 80 was suddenly ended. Through Audi-NSU-staff a few 871-engines have made it to the market. Some members of present Ro 80-clubs in the German-speaking countries have been so lucky as to have laid their hands on one of these power plants. ●

Engine two-disc rotation engine

Capacity 995 cc

Max. power 85 kW/115 bhp at 5.500 rpm

Max. torque 162 Nm at 4.500 rpm

Top speed 180 km/h (120 mph)

0-100 km/h (0-60 mph) 13.0 s*

Kerb weight 1.280 kg

Price (1974) Dfl 25.500 (E 11.435)

*According to manufacturer

As a 17-year old Felix Wankel (1902-1988) felt it would be a lot more efficient to make a four-stroke engine go through its four stages spinning instead of going up-and-down. At the age of 22 he made himself a lab, where he could develop this idea, even if he was no engineer. Wankel soon discovered that lubrication and sealing of the combustion chambers would be the main problems to overcome. Yet it would cost him nearly all of his lifetime to make his idea work.

In the meantime the national industry grew interested in his work. BMW made him an offer in 1934 to come and carry out his research in their labs, but they could not reach an agreement. In 1936 the German Ministry of Air Travel (RLM) offered him support. At that time Wankel had a working engine with rotary piston ready, which had raised a lot of attention at the RLM. Thanks to the RLM's support Felix Wankel could build a bigger laboratory, the Wankel Versuchswerkstatt in Lindau on Lake Boden. Soon afterwards the RLM's R&D-department built airplane engines with rotary pistons, the sealing components being developed by Wankel Versuchswerkstatt. The engines proved to be fine.

During World War II Wankel could carry on his research, compliments of the RLM's support.

In 1945 the allied forces dismantled his lab. It was not until 1951 that he took up his experiments again, this time in his own house, where he founded the Technische Entwicklungsstelle (TES). In 1957 the rotary engine was declared ready for production, but only in 1963 NSU introduced the first rotary engine driven car, the NSU Wankel Spider. It sported a single-rotor 500 cc engine, delivering up to 50 hp, which could propel the car to a top speed of 150 km/h. Mass production of the peculiar NSU started in 1964. Three years on the Ro 80 would follow in its tracks.

NSU have co-operated with Citroën, developing the Wankel engine. In 1964 these manufacturers founded the Comobil Company in Geneva with the purpose of jointly developing a passenger car driven by a rotary engine. In order to produce these engines the Comotor factory was established in Luxemburg in 1967. The Citroën M35, a sporty version of the Ami8, that never made it beyond the stage of prototype (1969), was built in this plant, as was the power unit of the Citroën GS Birotor, which did reach production stage. Citroën had planned mounting a rotary engine in the CX model, but that never happened, because Volkswagen, the new owner of NSU chose to terminate the Franco-German alliance in 1972.